In the previous post we had a first look at Kubernetes and deployed our hello world app on a local cluster using the CLI. The simple commands we used are good enough for a first taste. However, the full power of Kubernetes comes with using configuration files. Helm builds on top of that, taking these configuration files to the next level.

Let’s start with the deployment we created last time. We had created it with the command kubectl run. The equivalent YAML file for Kubernetes looks like this:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

spec:

replicas: 1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: blog-helm

spec:

containers:

- name: blog-helm

image: blog-helm

imagePullPolicy: Never

ports:

- containerPort: 3000

This file works fine and we can use kubectl create -f deployment.yaml to run it. The documentation has examples but also proper API reference for these objects. Please note that Helm builds on top of this, so this documentation is still needed.

Helm is a tool which builds on top of this. It calls itself “the package manager for Kubernetes”, a fair statement, as it allows us to package all the necessary YAML files into a single versioned entity called a Helm chart. It offers a templating language, which allows us to keep our Helm chart generic. Thanks to that, we’ll be able to deploy our application on multiple environments (think DTAP) without much effort. And all this without inventing its own syntax; it builds on top of the Kubernetes configuration.

Let’s give it a try. First, you’ll need to install Helm (e.g. brew install kubernetes-helm, unfortunately no Chocolatey package yet). Note that Helm has a client-side part, but also a server-side part, which is called Tiller. Helm uses Tiller to manage its releases. Make sure you install that with helm init:

PS> helm init

$HELM_HOME has been configured at C:\Users\ngeor\.helm.

Tiller (the Helm server-side component) has been installed into your Kubernetes Cluster.

Happy Helming!

Give it some time while it installs itself in the minikube cluster. You can monitor progress with kubectl get pods -n kube-system:

PS> kubectl get pods -n kube-system

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kube-addon-manager-minikube 1/1 Running 0 5m

kube-dns-6fc954457d-97wtm 3/3 Running 0 5m

kubernetes-dashboard-5zfj6 1/1 Running 0 5m

tiller-deploy-cffb976df-rm4l7 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 0s

PS> kubectl get pods -n kube-system

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

kube-addon-manager-minikube 1/1 Running 0 12m

kube-dns-6fc954457d-97wtm 3/3 Running 0 11m

kubernetes-dashboard-5zfj6 1/1 Running 0 11m

tiller-deploy-cffb976df-rm4l7 1/1 Running 0 6m

Let’s create the Helm chart for our hello world application. Start by creating a folder called helm (or any name you want) and inside that folder let’s create our chart with helm create blog-helm:

PS> mkdir helm

PS> cd helm

PS> helm create blog-helm

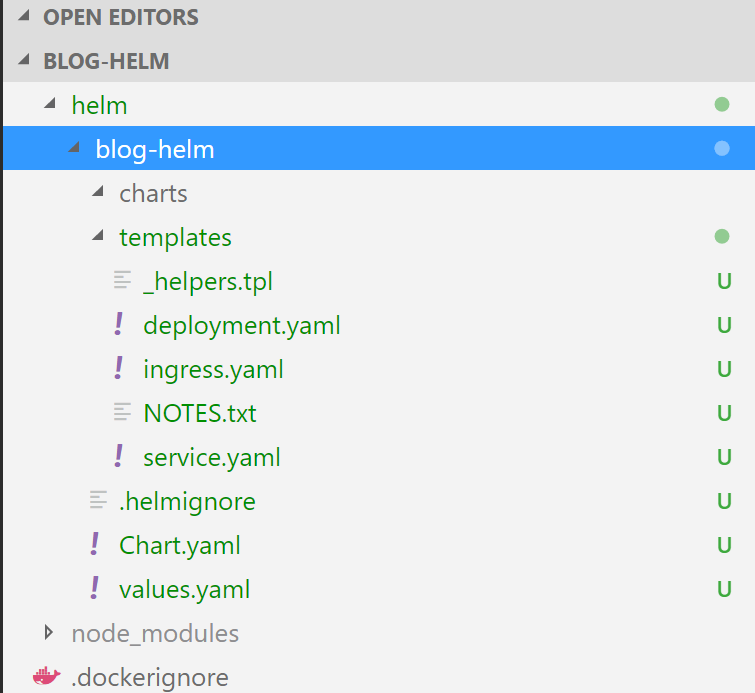

We get a bunch of new files (browse code at this point):

.helmignorewill be used to ignore files when packaging the chart. It's similar to.gitignoreand.dockerignore.Chart.yamlis the main file of the chart. It's mainly there to identify the chart's name and its version.values.yamlis a set of values that can be used in the templates of the chart. You can specify here whatever values you want. The interesting thing is that when you're using the chart, you can override these values. We'll see how this works great when modelling environment specific configuration for deploying to multiple environments on a next post._helpers.tpldefines some handy helpers that can be used in the templates.deployment.yaml,ingress.yamlandservice.yamlare templates which describe our Kubernetes deployment, ingress and service respectively.NOTES.txtwill be used to display a help message when we'll install the Helm chart.

We can have a look at service.yaml:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: {{ template "fullname" . }}

labels:

app: {{ template "name" . }}

chart: {{ .Chart.Name }}-{{ .Chart.Version | replace "+" "_" }}

release: {{ .Release.Name }}

heritage: {{ .Release.Service }}

spec:

type: {{ .Values.service.type }}

ports:

- port: {{ .Values.service.externalPort }}

targetPort: {{ .Values.service.internalPort }}

protocol: TCP

name: {{ .Values.service.name }}

selector:

app: {{ template "name" . }}

release: {{ .Release.Name }}

The templating syntax of Helm is based on Go templates. The go language is attracting a lot of attention these days and coincidentally all these tools are written in go. Some quick observations:

- we can reference values found in

Chart.yamle.g..Chart.Name - we can reference values found in

values.yamle.g..Values.service.name. Keep in mind again that we can provide overrides when rolling out the app with Helm.

Let’s see our values.yaml:

# Default values for blog-helm.

# This is a YAML-formatted file.

# Declare variables to be passed into your templates.

replicaCount: 1

image:

repository: nginx

tag: stable

pullPolicy: IfNotPresent

service:

name: nginx

type: ClusterIP

externalPort: 80

internalPort: 80

ingress:

enabled: false

# Used to create an Ingress record.

hosts:

- chart-example.local

annotations:

# kubernetes.io/ingress.class: nginx

# kubernetes.io/tls-acme: "true"

tls:

# Secrets must be manually created in the namespace.

# - secretName: chart-example-tls

# hosts:

# - chart-example.local

resources: {}

# We usually recommend not to specify default resources and to leave this as a conscious

# choice for the user. This also increases chances charts run on environments with little

# resources, such as Minikube. If you do want to specify resources, uncomment the following

# lines, adjust them as necessary, and remove the curly braces after 'resources:'.

# limits:

# cpu: 100m

# memory: 128Mi

# requests:

# cpu: 100m

# memory: 128Mi

By default, it doesn’t install our application but it installs nginx. Let’s fix this:

image:

repository: blog-helm

tag: latest

pullPolicy: Never

And also we need to change the service type to NodePort and adjust the internal port:

service:

name: blog-helm

type: NodePort

externalPort: 80

internalPort: 3000

Now that we have our Helm chart (browse code at this point), we can use it to deploy our application:

PS> helm install ./blog-helm

NAME: callous-koala

LAST DEPLOYED: Mon Nov 27 19:46:16 2017

NAMESPACE: default

STATUS: DEPLOYED

RESOURCES:

==> v1/Service

NAME CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGE

callous-koala-blog-helm 10.0.0.223 <nodes> 80:30129/TCP 1s

==> v1beta1/Deployment

NAME DESIRED CURRENT UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGE

callous-koala-blog-helm 1 1 1 0 1s

NOTES:

1. Get the application URL by running these commands:

export NODE_PORT=$(kubectl get --namespace default -o jsonpath="{.spec.ports[0].nodePort}" services callous-koala-blog-helm)

export NODE_IP=$(kubectl get nodes --namespace default -o jsonpath="{.items[0].status.addresses[0].address}")

echo http://$NODE_IP:$NODE_PORT

Since we didn’t provide a name, Helm generates a release name automatically (callous-koala).

Note that the only file we had to change is values.yaml. That’s because the default chart that gets generated automatically by Helm is quite a good starting point.

We can delete the release with helm delete --purge callous-koala. If we want to install it again with a predictable name, we can run helm install ./blog-helm --name blog-helm. We can see the releases we have with helm list:

PS> helm list

NAME REVISION UPDATED STATUS CHART NAMESPACE

blog-helm 1 Mon Nov 27 20:01:34 2017 DEPLOYED blog-helm-0.1.0 default

And we can upgrade an existing release if we want to with helm upgrade.

While this is all very nice and interesting, we are far from implementing a continuous deployment pipeline. We’ll start doing that in the next posts. The main points to think about is to see what our artifacts are, how to version them and how to support multiple environments for deployments. The goal is to be able to use Helm to deploy whatever (whatever branch), wherever (any environment).