As a Greek developer, I learned early on the importance of character encodings. But even in the age of Unicode, troubles still exist.

Back in the days of DOS, Greek support was tricky. The code page 737 was used to map the upper half of the ASCII table into Greek characters. Then Windows came along, but it used a different mapping, the Windows-1253 code page. This was incompatible with the DOS code page. So a text file from the DOS era needed to be converted to Windows. During the DOS / Windows 3.11 times, where you might need to switch back and forth, that was not fun.

To further complicate things, the official ISO standard for Greek, ISO 8859-7, was almost identical to Windows-1253 with the notable exception of one character: Ά (capital alpha with accent). It was easy to spot the difference. The character was coded as byte 182 in the ISO standard, which mapped to the end of paragraph mark (¶).

I was only using DOS / Windows in the era before unicode, so I can imagine there are more complications if we go to the Mac / Unix world of that time.

It’s not surprising that during that time people on the internet (and not only there) preferred to use “Greeklish”, which meant using the Latin alphabet to type Greek. So instead of typing καλημέρα (good morning), you would type kalimera. But there are more than one ways of mapping Greek to Latin, which lead to further fun at that point.

It is sufficient to say that Unicode was a big relief. You finally had one standard that got rid of all ambiguity. On top of that, you could combine multiple languages in the same document (e.g. French and Greek), because they were no longer competing for the same upper half part of the ASCII table.

For a developer, this also meant new challenges. A unicode application could reach more users in more markets, but some languages are more special. A notable example in programming has to do with the Turkish i. The Turkish alphabet has both a dotted and a dotless version of i. The saying was: don’t claim your application works for all languages until you’ve tried it with Turkish.

Back to the Greek language, I was very surprised some time ago when I discovered that actually not all ambiguity was gone. I was writing a small program to create a music playlist. The program would read a text file containing a list of song titles. Then it would scan my iTunes library to find matches. Every song that matched was copied to a folder. Then I would drag and drop the folder to my Android phone. Easy peasy.

It worked fine for almost all songs, except the ones that contained Greek letters with accents. For example, the word Αυτό (That, pronounced afto). It just didn’t pick it up from the file system.

Back to programming principles:

- it's always your code's fault

- if you have a bug, you're missing a unit test

So I added the unit test, which also failed. Starting to doubt my sanity, I added a test that compared the two strings. The string from the text file and the string from the file system. The unit test failed again, indicating that the two identically looking strings were, in fact, different. With eyes wide open, I confirmed with a Hex editor that the filesystem was using a different way of representing the accented letter. Historically, since the DOS days, a Greek letter with an accent would hold its own place in the mapping table. The letter ό in our case (lower case omicron with accent) is no exception and has the place 972 in the Unicode table. In the file system however, it was represented by two unicode characters: the lower case omicron without accent (959) plus the accent as a separate combining character (most likely character 714, Modifier Letter Acute Accent).

I can’t even begin to understand why somebody thought this was a good idea, but the XKCD comic about standards is always a handy reference.

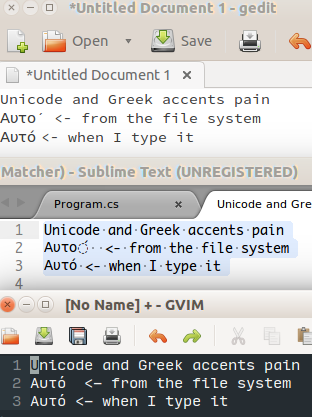

I even managed to find some text editors that couldn’t cope with representing the two unicode characters as one, rendering it a bit weird:

In gedit, it showed the accent as a separate character. In Sublime, it showed the accent as a kind of phantom character, which I think makes the most sense. Vim just does its job as it should and so did Visual Studio that I was using to write my small playlist program.

Luckily, my playlist application was written in .NET, which has support for this kind of mess. You can normalize a string, to use either of the two forms. The one where only one character is used is called composition, the other one is called decomposition.

It’s probably funny how difficult it is to handle properly basic human needs like language and time (timezones) in computers.

Fun fact: in Windows 10, I need to exclude my iTunes library from the File Backup, otherwise it dies. We still have a long way to go before “tea, earl grey, hot”.