The term microservice has been getting a lot of hype and attention. I have to admit that I fail to understand what’s the big deal about it. The best practices about microservices are similar to the ones we should apply to everyday software design. Avoid tight coupling. Single responsibility principle. Keeping things simple. Even those principles go back to the old Unix mantra of doing one job and doing it well (and that’s from 1978). And even that could in turn be labelled just “common sense”.

At some point, the hype and the buzzwords settle down. The overly excited hype driven developers come down from their high and realize they still have to deliver the business features they’re being paid to deliver. Work is work and it needs to be done. The problems you’ll need to solve are again old problems, despite how new and fancy your technology might be. Size of your services does not matter, at least when it comes to communication. Micro or nano or pico, once you have more than one service, they’ll probably need to talk to each other. Communication between services is such an old problem.

You might think that the most obvious way of communicating is the venerable HTTP protocol. SOAP, REST, or something else, HTTP is a pretty straightforward way for two services to start talking. I have to say however that in eCommerce, in my short experience in the field, the ancient HTTP is as far as science fiction. We’re still exchanging CSV files (or even worse some proprietary formats) over SFTP (or even worse FTP), because that’s what our vendors use. There’s a lot of room for improvement here. A good use case for a microservice is to abstract vendor specific communication protocols and formats. But let’s go back to the HTTP protocol.

The problem with HTTP is that if the service you’re trying to call is down, you get an error. Depending on the nature of the call, that could arguably be a good thing. Perhaps you do in fact want to fail immediately if the service you’re calling is off. But usually, you’ll want to retry. Usually, you’ll want to try the call again, until you get a response.

Implementing this kind of retry logic can be tricky and error prone. Defining rules for the retrying logic is not a small task either. It can even be many orders of magnitude bigger than the business task you’re trying to implement.

When left unattended, many developers fall into this trap. Sometimes it’s due to inexperience (they don’t know any other way), sometimes it’s due to the wrong mentality (they write code or try new things because it makes them happy). In my mind, the wrong mentality counts also as inexperience. I like to quote Dijkstra on this (if we wish to count lines of code, we should not regard them as “lines produced” but as “lines spent”). The less code I have to write (and test, and review), the better. Should be common sense?

So, before we reinvent the wheel and implement custom retry logic for HTTP, let’s see the next communication technique: queues. A queue accepts messages from the sender (who is called the producer) and stores them until the receiver (who is called the consumer) requests them. If your HTTP call is already fire and forget, meaning you don’t care immediately for a response by the service you’re calling, then it’s quite easy to switch over to use a queue. If however you must wait for a response, then you can’t use a queue directly. You’d have to re-architect the sender, so that it can receive a response without waiting.

There are many queue implementations, like RabbitMQ, Amazon SQS (Simple Queue Service), etc. You can see a list of some of them here (it’s a pity they don’t mention MSMQ, they first queue I ever used). Features of them also vary. For example, some queues guarantee that the messages will arrive in the same order as they were sent, others don’t. Usually, you have a dead letter queue, which collects messages that failed to be processed. At work, we use AWS for all sorts of things, so the rest of the post focuses on Amazon solutions.

A very interesting problem arises when the messages in the queue can be useful to multiple consumers. Since we’re doing microservices, it might very well be the case that more than one microservice will be interested in the messages of another microservice. To use an eCommerce example, let’s say that a parcel has been shipped to the customer. One microservice might want to charge the customer’s credit card and another one might want to send an email to the customer, telling her the parcel is on its way. Both these microservices would like to listen to “parcel has been shipped” kind of messages.

If it’s a single consumer, things are simple. The consumer reads the message. If it can be processed successfully, the consumer then deletes the message from the queue. If something fails, the consumer moves the message to the dead letter queue. What will happen however if multiple consumers try to process the same message? What if a consumer is really fast and deletes the message before the others have a chance at reading it? Some coordination perhaps is needed to indicate that all consumers finished processing? And how will these consumers talk to the coordinator? Hopefully, you’ll see what’s going on here. It’s the same trap as before. Just like with the retrying mechanism for HTTP, this coordination can be a problem orders of magnitude bigger compared to the business value. If the queue implementation doesn’t provide it out of the box as a feature, then you should change to a different implementation.

How does Amazon SQS deal with multiple consumers? Once a consumer reads a message, it is hidden for a certain amount of time (visibility timeout). The message stays in the queue, it is not deleted. It is hidden. It will appear again, if the consumer fails to delete it in time. The purpose of this is to facilitate horizontal scaling. You can have multiple consumers processing the messages in the queue. However, this is not our use case. We want different microservices to process the same message, not different instances of the same microservice. The multiple consumer support of SQS is meant for multiple consumer instances of the same microservice. So this doesn’t solve our problem.

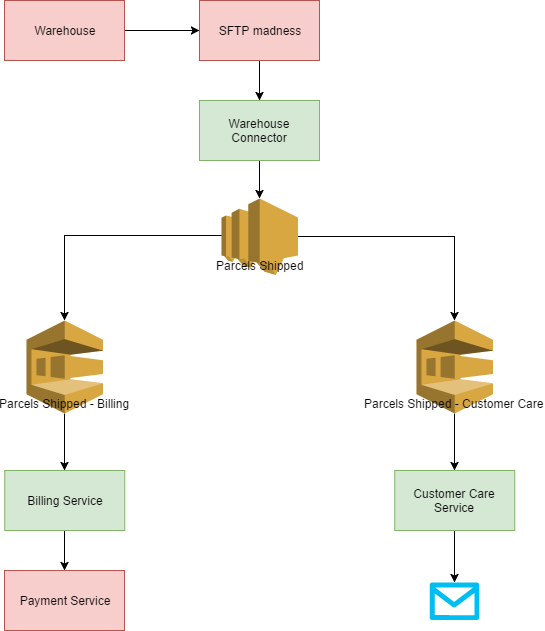

To provide this functionality, we can combine the powers of SQS with SNS (Simple Notification Service). Instead of publishing a message to an SQS queue, we’ll publish it to an SNS topic. For each consumer microservice, we’ll have a dedicated SQS queue. And the glue is provided by AWS: it is possible to subscribe an SQS queue to an SNS topic, meaning that a message published to an SNS topic gets sent to all subscribed SQS queues. The following diagram shows this in action:

The red blocks are external systems, the green blocks are our microservices.

- The warehouse connector polls the SFTP folder and reads the proprietary text formats. When the warehouse ships a parcel, the connector publishes messages on the SNS topic "parcels shipped".

- Amazon takes the SNS messages and publishes them to the subscribed SQS queues.

- The billing microservice polls its queue for messages and calls the payment service in order to charge the credit card of the customer

- The customer care microservice also polls its own queue and sends an email to the customer

Note that these microservices can also scale horizontally, since they have their own dedicated queue (and thanks to the visibility timeout of SQS).

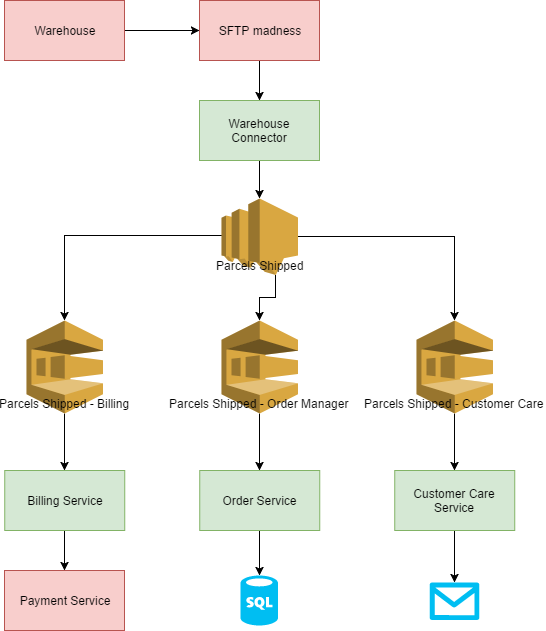

What if we want to add one more microservice that listens to these parcel shipped messages? We don’t have to change anything in the existing microservices. We need to add one new SQS queue and subscribe it to the SNS topic:

This new microservice maintains a state of the orders and updates a good old fashioned traditional relational SQL database (I survived the NoSQL hype as well).

What about Kafka and Amazon Kinesis? I have virtually no experience with these technologies. The more I read about them, the more I see they’re targeted to a different audience. They solve problems related to Analytics and Business Intelligence. Kafka indeed offers a publish-subscribe model, which has out of the box support for multiple consumers. But in my mind, it can be an overkill. Kafka and Kinesis, from what I can understand, are meant to deal with a huge amount of data coming in at a very high pace. By huge I mean that you want to know for every user of your website or mobile app where/what/when she clicks, how long they stay on a page, etc. Just imagine how many messages you’d have to process per second. If you need it, go for it. If you’re processing “parcel shipped” messages? You probably don’t need it.

When you don’t know a technology, my advice is to start small and change when it doesn’t fit you anymore. Don’t disrespect REST/HTTP. It might be the correct communication protocol for your needs. It can also serve as an excellent prototype to get the ball rolling fast. Do you really need multiple consumers? Are you designing for something that doesn’t really exist? Remember YAGNI. Maybe the next logical step is to go for a simple queue if you want to decouple services. If you’re already invested in AWS, as we are at work, why not explore the managed (buzzword lingo: serverless) technologies it offers first? If your argument is scale, do you know what volume your services are expected to handle? Or is it another case of hype-driven-developers over-engineering? Keep it simple stupid and all these old mantras are easier said than applied.