When you are the maintainer of an npm package, you need to do some administrative work around its versioning. When you release a new version, you need to make sure the package.json is updated, the package is correctly uploaded to npm registry, the git repository is tagged accordingly and so on. You shouldn’t be doing these things manually if you can automate them.

First of all, let’s assume you’re using GitHub Flow as your branching strategy. Let’s also assume you already have a build plan in your continuous integration server that makes sure that your branches are green. We are not going to look into that in this post; we take for granted that you have already guaranteed that a green branch can be merged into master and that is enough for having a deployable release.

You should of course only bake releases out of your master branch. Don’t modify your existing build plan to create releases as well. Keep the existing build plan focused to its purpose, which is to ensure the quality of your feature branches. You should create a new build plan, dedicated for the master branch only, which will handle post-merge tasks, like triggering deployment and versioning. Otherwise, you’ll end up complicating the main build plan with conditional logic based on the branch name, which makes it difficult to read and maintain.

npm packages already have a version specified in their package.json file. There are various options for determining the version to use:

- just use the version from the

package.jsonfile. It is the developer's responsibility to bump it up accordingly. - take the major and minor versions from

package.jsonbut use an auto-generated number for the patch component of the version. So ifpackage.jsonindicates version 1.0.0 and the CI server runs build 42, the resulting version should be 1.0.42 - define the version when you start a deployment (manually typing the version in a parameterized build plan)

The first option is very simple. The developer is responsible for maintaining the package.json. The source code is always aligned with reality. No magic numbers coming from the CI server. The problem however is that you do need that extra commit to change the version when you’re releasing. This prohibits automatic continuous deployment. In other words, you will not be able to automatically deploy every green master, simply because the version number wasn’t modified.

The second option solves the problem of the automatic deployments. As soon as you have a green master, a new build is triggered. The patch component of the version is calculated on the fly (which needs a bit more work to implement). The problem here is that your source code doesn’t have the accurate version number. The package.json is not reflecting the latest version, which could be confusing. It might also lead to developers releasing code that breaks compatibility with previous versions without upgrading the major version number.

The third option is used when you don’t care for automatic continuous deployment and you also don’t like the CI server automatically supplying the patch version component. In this option, you are performing a manual release whenever you see fit and you provide the version manually.

Let’s see how we can implement the first option in Jenkins, with an extra safeguard that will break the deployment if the version hasn’t been bumped up in package.json.

First, the Jenkins user should have the right to publish the npm package to the public npm registry. You need to login to the CI server and, executing as the jenkins user, you need to login to npm. That’s done with the npm login command. If the jenkins user isn’t logged in to npm, publishing of the package will fail.

We want to prevent re-publishing the package if the version in package.json has not changed. For that, we’ll compare the information in package.json against the information that the public npm registry provides us. That’s done with the npm view command. If the version is already there, then we fail the build immediately.

If everything is fine, we proceed to publish the npm package with the npm publish command. Finally we tag the version in git. Jenkins has a plugin for that so we don’t need anything here.

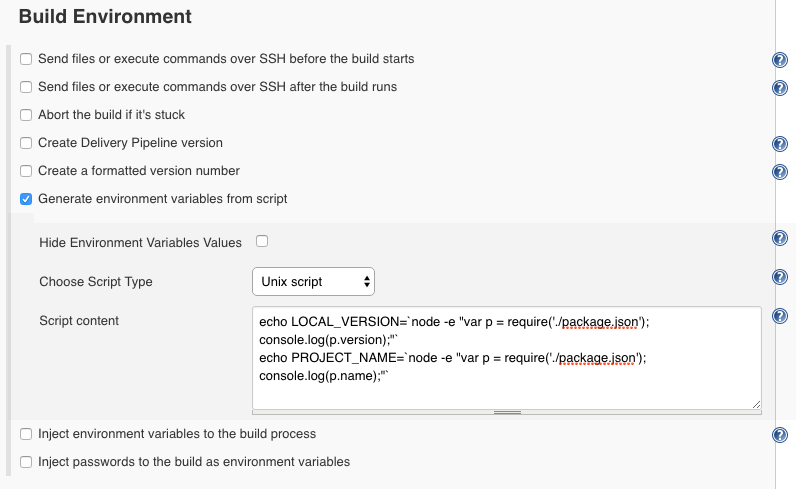

Let’s see this in action. We use a script to read the package.json. We extract the version and the project’s name and store them in environment variables.

echo LOCAL_VERSION=`node -e "var p = require('./package.json'); console.log(p.version);"`

echo PROJECT_NAME=`node -e "var p = require('./package.json'); console.log(p.name);"`

We’ll use these variables in the build step but also in the post-build to tag the version in git. Note that the above is made possible with the Environment Script Plugin (in Jenkins, you need quite some plugins to get things done).

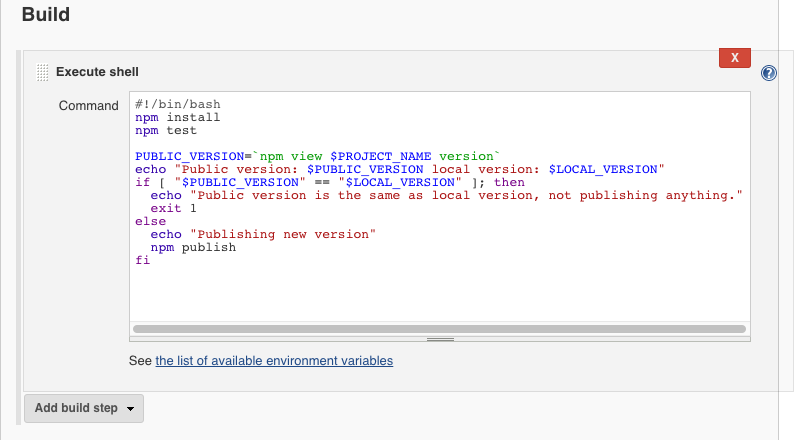

The build step is responsible for publishing the npm package, as long as the version hasn’t been published. It’s a bash script:

#!/bin/bash

npm install

npm test

PUBLIC_VERSION=`npm view $PROJECT_NAME version`

echo "Public version: $PUBLIC_VERSION local version: $LOCAL_VERSION"

if [ "$PUBLIC_VERSION" == "$LOCAL_VERSION" ]; then

echo "Public version is the same as local version, not publishing anything."

exit 1

else

echo "Publishing new version"

npm publish

fi

The echo statements are for diagnostic purposes. It also does npm install and npm test as an extra precaution, but this really should work if the main build plan had passed the build.

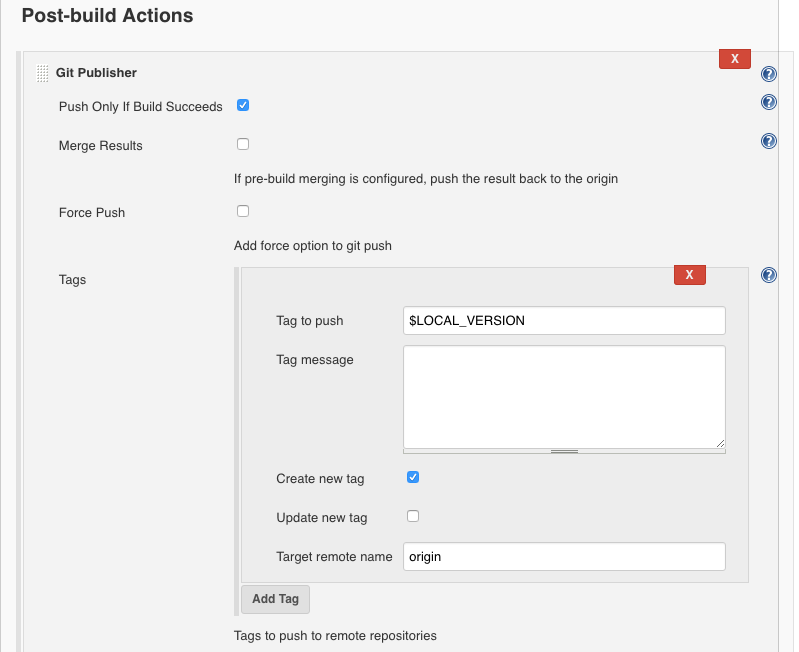

The last step is to tag the version in Git. This is done with the Jenkins Git plugin (most likely you’ll already have this one installed).

Note that we’re using the LOCAL_VERSION environment variable that we populated with the information coming from package.json. Also, the tag will only be published to git if the previous steps succeeded. In other words it won’t tag anything in git if publishing the package to npm fails. Finally, the ‘update tag’ checkbox is disabled, which means that the build will fail if the same tag already exists. Just another sanity check that shouldn’t happen.